Why We Need Guilt Right Now

Unity may seem like a noble cause—but in reality, it's an evasion of a hatred that needs confronting.

One of the more frustrating byproducts of the past four years (or eight, or 12, depending who you ask) is that reality has been distorted by misinformation campaigns, social media algorithms, and media polarization. This makes it very hard to collectively address and reckon with what’s really wrong in our society, and harder to figure out how to move forward together. In the aftermath of an attempted coup, maybe you’re asking yourself the same question I am: Where the hell do we go from here?

After a couple of conversations with friends and scholars about my frustrations, I wanted to look back to another time a nation tried to reckon with its division, atrocities, and hatred. That’s how I found (via the fine folks at The Holocaust Museum) Katharina von Kellenbach, professor of religious studies at St. Mary’s College in Maryland. Von Kellenbach is the author of Mark of Cain: Guilt and Denial in the Post-War Lives of Nazi Perpetrators, which explores the crucial role guilt plays in reconciliation. “Guilt is the door towards change — not forgiveness,” von Kellenbach told me.

I was so moved by our conversation — which covers everything from reparations to historical revisionism — that I am publishing it here as a Q&A. Our questions and answers have been edited for brevity and clarity. I hope you find it somewhat useful in these very confusing times. If you ended up here from social media or an e-mail forward, please consider subscribing via the button below.

Phillip Picardi: Can you provide me with some historical context of what happened after the Holocaust, and what Germany did to reckon with or confront the damage and the genocide that it had caused?

Katharina von Kellenbach: The most important thing that happened is that they were defeated on the battleground and occupied. Germany was a militarily defeated, occupied country. It signed a total capitulation and was occupied by the Allied Forces, and the United States had taken the leadership to institute a legal program of accountability. The Nuremberg Laws were written in the beginning of 1943. There was an international military tribunal to try the main perpetrators, and there were three counts: the war, crimes against humanity, and crimes against peace. The decision to have a legal accountability program was driven by the United States, but the French, the British, and the Soviets signed up and did it also.

But when you look at the different trial programs, the Americans were the most thorough when it came to denazification. There was both the international military tribunal and then there was a denazification campaign. Everybody who served in public function had to go before local tribunals and say whether they were members of the party and how they had collaborated, and then there were different degrees of complicity. There was a professional ban; you lost your employment. That affected university professors, teachers. Never the lawyers, actually. And then that whole thing collapsed very quickly, because it was totally unwieldy and it riled up the entire population into the arms of those who were truly guilty.

I was just looking up a book which is sort of relevant for this called The Culture of Defeat by Wolfgang Schivelbusch. He compares Germany to the American South, because the relevant question is: What went wrong with the Civil War? I mean, how did they lose and yet still end up parading the Confederate flag, and building all these monuments, and ultimately, not losing?

In so many ways, this is relevant to the current rise of neo-Nazism in Germany and throughout Europe. Do you feel like that comparison — Germany post-Holocaust and the South post-Civil War — is more apt than, say, Germany being a pinnacle of accountability and reconciliation after the Holocaust?

Germany is not the pinnacle of anything, but it was under extreme pressure. There were lots of trials — most of them pitiful because many of the perpetrators had actually totally integrated [into society]. After that initial prosecution enthusiasm or passion, whatever you want to call it, that energy totally dissipated. By 1958, all convicts of the Nuremberg trials who were not executed were released from prison. All of them.

It's interesting, because there was a lot of international attention and pressure on what was going on. Around the same time, Germany was integrated into NATO and the European Union, so there were lots of business incentives to actually come to terms and take things seriously. It was both a carrot and a stick approach at the same time. In the ‘60s, the German justice system gained permission and started prosecuting Nazi perpetrators. That's when the Auschwitz trial happened, the Einsatzgruppen trials. That is the big difference between Germany and the South, because [the South] did not have that kind of public, external pressure.

“What's there to forgive if

you don't ask for forgiveness?”

I think that gets to the heart of your current study, about the power guilt and shame have in bringing about transformation. What have you learned from this period of time about guilt and its efficacy?

I started with forgiveness, because I’m a theologian. I started looking at prison chaplains working with Nazi perpetrators, starting in '45. These chaplains understood themselves as missionaries, because many Nazis had left the churches and became SS. National Socialism had its own religious affiliation; they called themselves Gottgläubig, believers in God. So the chaplains would go into these prisons to basically reconvert the prisoners and teach them Christianity. And of course, they emphasized a message of forgiveness because that's what Christianity is about — Jesus died for your sins, so your sins are forgiven, and if you repent, everything is fine.

But the problem [with these prisoners] who had murdered on order, and on behalf of the legal authority of the state, was that they did not feel like murderers and criminals. There was no repentance. No contrition, no remorse. None. Nothing. I mean not a thing. And so that whole message of forgiveness? It just didn't go anywhere. Because they didn't ask for forgiveness.

They didn't want it.

They didn't want it. Meanwhile, of course, the Churches at the time were going on about how ‘the Jews don't forgive and it's all about revenge and retaliation.’ That's anti-Jewish Christian theology: that Christianity is all about forgiveness and a loving, forgiving God, unlike Judaism, which is all about wrath and vengeance and justice. And meanwhile, these guys, not a single one of them is asking for forgiveness! So what's there to forgive if you don't ask for forgiveness?

I was forced by my research to move back into guilt, and so the book I wrote is called The Mark of Cain. Cain gave me a different story to think about. Cain had a long life — he married, he had children. And he was given a chance, but only because he learns to live with guilt. I mean, he's marked! And that mark is a mark of protection, so he can't wash it off. Wherever he goes, he has to learn to talk about it. He has to find the language. At some point, his son asks him, "So what's with the mark?" So he had to talk to his children, to his wife, to the city that he built.

Cain gave me a different story, and led me back to guilt. Guilt is the door towards change — not forgiveness. Nobody forgives Cain. It's not a thing! And frankly, it's not a thing in Germany, either. It's not about forgiveness. That is the wrong entry and it's a dead end.

The way you frame that is really powerful. In my own studies, especially of non-Christian faith or even liberation theology, there is an understanding that repentance does not equal forgiveness. But now the question is — both today and back then — how do you teach someone to be guilty? What do you do with people who won't recognize their guilt?

In the German case, it was the children who inherited the guilt. The Bible is right: You [pass it down] to the third and fourth generation. To some extent, that's true for racism as well. Of course, the longer you wait to actually receive and then transform the guilt, the harder it gets.

For the book I’m working on now, I was intrigued by the language of cleansing, purifying, and washing. Forgiveness is understood as a sort of cleansing — to be cleansed in the blood of Christ or to wash your hands of guilt. I ended up thinking about washing, and through that, I thought about where the dirt goes. So now, I'm thinking about composting guilt. If you throw something away, it goes away, but it actually goes in a sewage plant. It’s not decontaminated. And if you throw something away and you don't decontaminate it, it actually grows more harmful. That's sort of what happens when you have something like slavery — a historical evil that has not been processed and transformed into something new that can serve as the ground of new being.

In Germany, to some extent, the decontamination has happened, which is not to say that the poison isn’t still there — it’s still there, and it's bubbling up again. But there is a general recognition that it requires ongoing engagement. It's not something to turn your back on. It's not something to run away from. It's not something to close off. It's something to be in active engagement with. And I'm just talking about the guilt — I'm not even talking about relationships to the victims, which is also important. The guilt requires its own process of engagement.

“You cannot evade evil —

you have to confront it.”

Right. But on the flip side, couldn't one look at this moment and think that, because we are losing our proximity to the past, doesn’t the Holocaust being a distant memory set the world stage for what we're living through now?

Yes. In other words, it is a matter of education and of how we engage the next generation. That's sort of the big question right now, especially since the first generation is passing. That level of immediacy is no longer there. The question is, how do we draw the next generation in so that they own it?

A complicated question. Unlike Germany, America has never had this extreme sense of shame around its history or its complicity in some of these hatreds. Would you say that that's a fair assessment?

It's not that there is less here in Germany. They have been parading Nazi symbols here too. But here, it's actually against the law. If somebody charges them, they will get convicted. There's this old woman here who is in prison because she denies the Holocaust. She's like 90 and she actually went to prison. But there were also neo-Nazis marching on November 8 to visit her in prison. In Germany, for neo-Nazis to march on November 8, that's not only a German problem but it becomes international news. That's front page news in The New York Times. Germany does not get away with this stuff. The struggle is just as real here as it is in the United States. It's just that here, the soil is blood-soaked.

To some extent, that's also true in the United States. I teach in Southern Maryland, which is also blood-soaked. We just unearthed slave cabins on our campus. So to have the Confederate flag fly in Maryland...that’s grounded in the place and its history.

As we enter a new presidency, Joe Biden has made a really deliberate effort to say that he wants to move toward bipartisanship. There have been calls across the board: "End the division. Let's come together in unity." Based on what you know from theology and your deep study of German history, what do you make of these calls for unity?

It's an evasion. You cannot evade evil — you have to confront it. And that’s not to say that you must shun the people necessarily, but you have to censure the evil and convict people. Once they're in prison, once they're out of power, once they have been removed, then you extend an invitation to conversation — not while they are in power and winning. Every time you engage, every time you let them get away with something, they're winning. They're not just getting away with it. They're actually winning a victory, and that's very dangerous.

It seems like political decorum is being prized over repentance and acknowledgement of reality. We're trying to act like there's been a peace treaty and there has been no such thing. What can the United States learn from Germany?

Reparations. Germany paid reparations to both collectives and individuals, and continues to pay reparations to the second generation. Reparations are an intrinsic part of repentance. From the perpetrator’s perspective, it’s actually liberating to disown the profit. For instance, a business that built gas chambers and is still operating today is making amends not only by publicly putting on their websites that they made the gas chambers, but they may also have a fund for education or exchange programs. It’s turning guilt into something that is life-giving and an investment in the future. But again, it's a matter of who will then be the recipient.

Germany paid money to Israel, to the state. Germany paid money to the Jewish Claims Conference and to the individuals who lost their property. Reparations payments changed over the years and is an ongoing process. There are some people who say, "Okay, it's 80 years later. When is it going to end?" Maybe that's an okay question. But Germany's a very wealthy country, and again, reparations are actually an investment. It's not about the past. It's about the future.

Reparations create new infrastructures, new growth in something. I think if America were to invest money in the Black community, in the descendants of slaves, that would grow new opportunities. People need to understand that reparations are not about punishment, but about investment and undoing the wrong — because every wrong has long-term consequences. It requires an acknowledgement of guilt. It requires an acknowledgement of the necessity for repentance and the benefits that accrue from repentance by way of investing in the victims.

America barely did the work with the Civil War, as you pointed out. There was no real repentance. So what kind of education and cultural institutions do we need to make sure that we emerge from these past four years with some sense of how to move forward and not repeat this past?

The history of racism has barely been written compared to the history of the Holocaust. I mean, when you look at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, it created an enormous center for scholarship. The same is true for some of the historical scholarship produced in Germany, which was partially paid by the German government and German businesses.

The African American History and Culture Museum in Washington, D.C. has begun to make a difference in producing historical scholarship, but the fact that we had a Holocaust museum before we had an African American museum tells you everything you need to know. The Holocaust museum was built in America and not in Berlin — meanwhile Berlin had three different museums dedicated to history of slavery in the United States. We need institutions to build the basic foundations for knowledge and research.

The second question is: How do you teach that? Where do kids learn where the plantations are. Where the auction blocks for the trade in enslaved people are located. Where people were lynched. That basic history is often not taught. So that would be really important. In Germany, this history is more public: we have the stumble stones, for instance. There are markers where Jews once lived, where the synagogues used to stand. The concentration camps have been turned into memorial sites. This history is present. If we had a little bit more history here in the States, I think the conversation about slavery and racism would change.

Third, how we deal with this global network of racism and neo-Nazism, which is now digital — that's a challenge that we have not yet fully confronted. These social media companies, something needs to happen there. So those are three large things about moving forward: Reparations, research and education, and how to rein in these social media giants.

THREE QUICK THINGS:

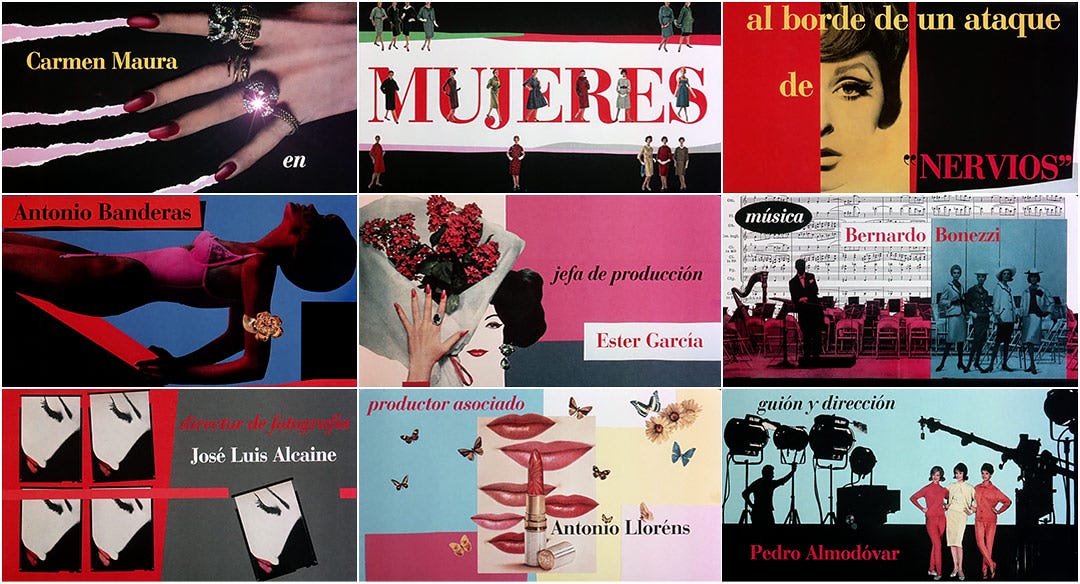

After finishing Gilmore Girls, I decided to NOT hop back into a television show binge, and instead put out a massive call for movie recommendations (with a very strict criteria) on Instagram. I got a lot of great suggestions, but kicked off the month by watching Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown by Pedro Almodóvar for the very first time. Please enjoy these visuals of the opening sequence, which will forever inspire me. I’ll publish a list of the films sent to my attention in the next couple of weeks — and yes, I’ll be taking more suggestions!

After working for over nine months to bring The Oral History of Fashion’s Response to the AIDS Crisis to life for Vogue, I was nominated for a GLAAD Media Award. It’s an honor, and if you haven’t spent time with the piece yet, I hope you will make some time.

In an essential piece about medical ethics, Dr. Steven Thrasher urges us: If you’ve been working from home, please wait for your vaccine. (Unbelievably, people are skipping the line and using their connections with doctors and hospitals to get early access.)

NOW READING: Still making my way through Cosmos & Psyche, but I also started The Autobiography of Malcolm X on audio. It’s a vocal performance by actor Laurence Fishburne, so it is quite a worthy listen. I also picked up a (very rare, very expensive) copy of Witchcraft and the Gay Counterculture.

PARTING WORDS:

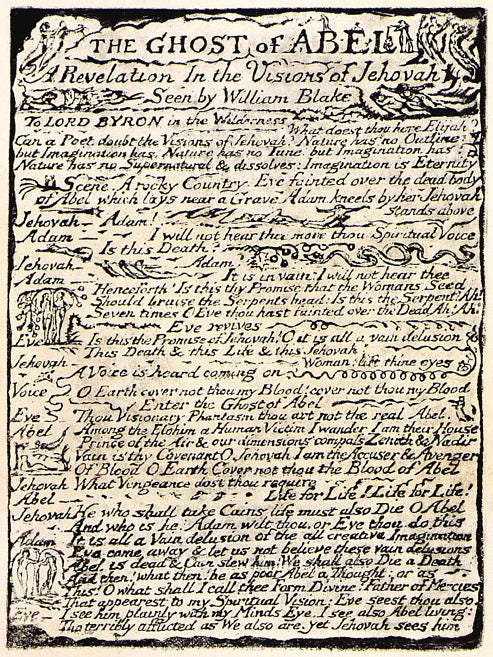

Of course, soon after I got off the phone with Katharina, I picked up The Complete Illuminated Books by William Blake and ended up on a piece about Cain and Abel. In this poem, Blake imagines the aftermath of Abel’s murder and invents a scene between Jehovah, Adam, Eve, Satan, and the Ghost of Abel. You can read the full text here, but below is how Blake intended for his poetry to be received: gorgeously etched in relief, often accompanied by illustrations of his own design. You’ll see the poem expresses a distinctly Christian theme of divine forgiveness—but that even God’s forgiveness won’t save Cain from a life of torment.