Who the Hell Cares About Fashion Right Now?

Our clothes have never mattered less. But that doesn't mean Fashion is any less important in this moment.

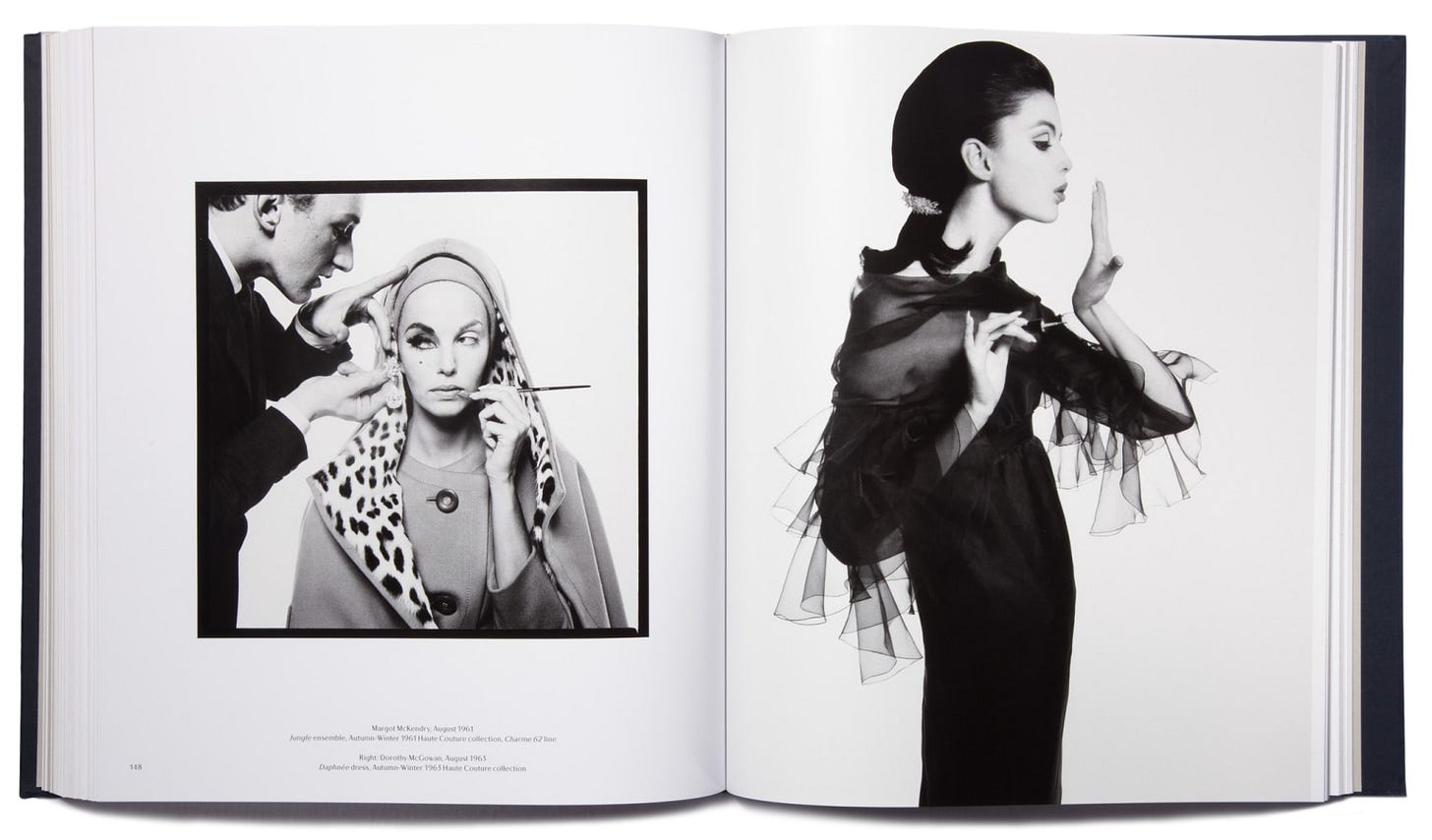

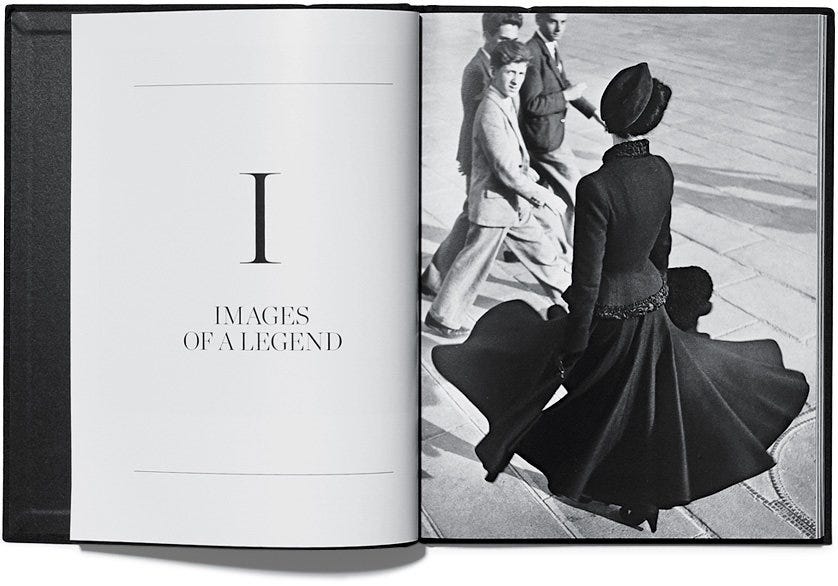

A scan from Dior by Avedon, via Rizzoli.

“What happened?” I asked, first to myself, then to anyone within earshot. I had just traveled my way through an exhibit at the Museum of FIT called “A Queer History of Fashion: From the Closet to the Catwalk,” and I was having the time of my life. According to its brochure, this was “the first museum exhibition to explore in depth the significant contributions to fashion made by LGBTQ individuals over the past 300 years.” I devoured every inch of it, making my way from the dandyism of Oscar Wilde to the nipped waists and voluminous silhouettes of Cristóbal Balenciaga and Christian Dior’s New Look. I swung through the ‘60s, marveling at the Marlene Dietrich-inspired motifs of Yves Saint Laurent and landed in the sumptuous disco of the Halston-era ‘70s. Then, a true feast of the eyes: the 1980s, complete with shoulder pads, sequins, and over-the-top glamour, ushered in and perfected by the likes of Gianni Versace. Greedily, I consumed every single caption, trying to commit the details to memory.

But then, rather abruptly, I arrived in a stark white space, where the magnificent gowns and excessive glamour turned to subtle, restrained minimalism; the color palette from celebratory to stark. “What happened?” I asked, and then found my answer in the text on the wall. “The AIDS crisis marks a turning point in the exhibition, as it did in reality,” my brochure read. “Many designers died of AIDS, including Perry Ellis, Halston, and Bill Robinson. But the LGBTQ+ community united in protest, as witnessed by activist t-shirts.” It became clear that during the AIDS Crisis, Fashion reeled from the impact; its luminaries, leaders, and artists lost. I gazed at a hallway of clothes devoid of ornamentation, lacking the gifts of the queer people who were no longer alive to spread their magic. It all looked like funeral wear; like Fashion was in mourning.

The display at the exhibition that day was, in reality, just one snapshot of what happened to the Fashion industry during the AIDS Crisis of the ‘80s and ‘90s, but it was certainly an apt one. It is this moment I keep coming back to in recent times, when the impact of coronavirus is not just being felt in the halls and intensive care units of our hospitals, but also on our economy. Fashion, of course, will be one of many industries impacted.

According to Business of Fashion’s State of Fashion report, most brands can expect to be down in revenue this year by an average of between 30 and 50 percent. If people are shopping, it is hardly for designer ready-to-wear—rather, explains BoF executive editor Lauren Sherman, it’s “things you’d expect: loungewear, beauty, at-home maintenance stuff like manicure kits, and activewear.” Fashion Weeks internationally have been either canceled or postponed indefinitely, with many of the luxury juggernauts pivoting their factories and resources to make either sanitizer or masks for healthcare workers. Across the industry, layoffs and budget cuts are already being felt, if not otherwise dreaded to be coming soon. Many brands, designers, editors, models, influencers, photographers, and more are forced to find new footing on more precarious ground: What, exactly, do we do now? What is our purpose at this moment?

I think we can find at least some of our answers from the AIDS Crisis, which is an imperfect but timely comparison to our current pandemic.

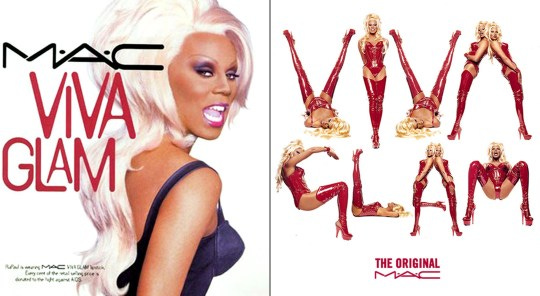

Some of our industry’s then-young leaders mobilized accordingly, united in both their grief and their outrage. MAC Cosmetics used its Christopher Street store as a haven for members of the community impacted by the virus, staying open late to help partygoers cover up lesions so they, too, could dance the night away with their loved ones. Eventually, MAC birthed Viva Glam, a lipstick and national advertising campaign featuring the drag queen RuPaul Charles, which donated 100% of its proceeds to charities helping to serve those impacted by HIV/AIDS.

Then, there was Bloomingdale’s, who helped out the then-fledgling charity called God’s Love We Deliver by lending its restaurant kitchen to cook Thanksgiving turkeys, all so bedridden or homebound people suffering from HIV/AIDS could have a proper holiday meal. And the CFDA threw the Seventh on Sale AIDS Benefit at the 26th Street Armory, co-chaired by Anna Wintour, Ralph Lauren, Donna Karan, and Calvin Klein, where New York’s designers came together to sell their wares, all in a spectacular fundraising effort. “When the tents went up, that reinforced our sense of community,” said Fern Mallis, then the executive director of the CFDA. “The tents became the heartbeat of the industry.”

“People had always thought of fashion as a very superficial industry, a models-and-parties business. That changed,” the stylist Robert Verdi told The New York Times. “Outside the industry, people started to realize when they ordered something from a catalog, that the copywriter, the photographer, the man who produces the paper it’s printed on, the man who delivers the mail, they are all part of the fashion ecosystem...AIDS galvanized us.”

It begs acknowledging that it was ACT UP’s organizers who pressured the government and pharmaceutical companies relentlessly for change—and in many instances, won. But Fashion, too, mobilized as a cohesive unit and was forever changed for it; the commitment to fighting AIDS is still embedded in our major institutions, from long-standing industry ties to Housing Works to the armies of models bringing attention to the AMFAR Gala, from the evolution of Viva Glam into a full-fledged Foundation, to Michael Kors donating an entire building to God’s Love We Deliver. Those young stars of the industry who organized then have now turned into titans, and they never forgot the people they lost along the way.

In times of crisis, it bears repeating: If there’s a lesson to learn, we can always look to where we come from. So it’s probably wise to start by saying that, no matter what, it will be hard to sell clothes—yes, even once things go “back to normal,” if they ever really do. Fashion learned this, to an extent, in the response to 9/11, when the CFDA mobilized accordingly. That’s why it’s especially crucial to face the more insidious parts of the industry that have long needed revolution. The past and present issues of our industry are not going to be swept away—in fact, they may only become more magnified.

Just like the AIDS Crisis once laid bare the public’s attitudes towards LGBTQ+ people, coronavirus has again shown us the mirror of a society that doesn’t care for its most marginalized. There is no world in which we emerge from this experience without a collective raising of consciousness. Consumers—even the wealthiest ones—will likely be wary of flaunting anything that could be considered excessive. Already, we see evidence of the public mindset shifting: victory gardens are sprouting on our window sills, campaigns are launching to support small businesses, magazine covers are celebrating healthcare workers instead of celebrities. There are people who think that this collective consciousness will evaporate quickly, so we can get back to the way things were. Unfortunately, they’re missing the point: Anyone yearning for a return to the “good old days” doesn’t realize that the days weren’t “good” enough for the rest of us.

Some of these new attitudes certainly threaten Fashion’s grip on power. If people were already motivated to “shop their values” before, just imagine how Fashion’s elitist attitudes towards beauty and the body will look to a public that’s been newly awakened to the one percent’s glaring privileges. Imagine caring about what’s being worn by “influencers” or “Kardashians” after you’ve spent months inside an ordinary home or apartment, gazing at their mansions and vacation properties through your iPhone screen. Imagine what it will mean to host a fashion show in some far-flung locale, placing hundreds of people on an airplane, when there is still a fear of spreading a virus, or of wasting carbon emissions to a world already ravaged by climate catastrophe. Imagine the reckoning that’s bound to come when consumers—horrified at the abuse and lack of safety nets for essential workers in America—realize that even our finest luxury brands are relying on unfair labor practices and sweatshops to deliver their goods.

If people were already motivated to “shop their values” before, just imagine how Fashion’s elitist attitudes towards beauty and the body will look to a public that’s been newly awakened to the one percent’s glaring privileges.

None of this has to spell doom for Fashion, unless the industry rallies around stagnation rather than embracing change. Just like a community assembled in the wake of AIDS, so too can Fashion find its purpose—it can embrace sustainability, meaningfully incorporate diversity into every sector of its business, support local artisans and laborers with ethical practices and fair pay, and reject the conventional norms of incessant collections in order to preserve the integrity of its artists and creators.

This last part is especially crucial, particularly if we want a viable industry once again, one where our designers overcome the odds and create something to make an anxious and wary public excited about clothes. “For the last 15 years or so, Fashion has been stagnant in terms of its ideas. There hasn’t been anything that’s changed the world. It’s morphed into something that’s much more about marketing,” Sherman says. “It would be incredible if some real creativity came out and made people think differently about how we dress.”

There is another period in Fashion history that’s relevant to our current moment—one that’s not just about how we answer to the now, but how we answer to what’s next.

On February 12, 1947, Christian Dior opened his couture house, debuting a silhouette that Carmel Snow, the editor of Harper’s Bazaar, dubbed “The New Look.” His collection featured dresses with natural shoulders, a fitted bodice, a nipped waist, and full, long skirts—a breath of fresh air among the more conservative forms of wartime dressing.

During the war, occupation officials in France limited the amount of fabric that could be used for a gown—thus, prompting the closure of many major couture houses. But now, liberated from wartime rationing, Dior could let his imagination run free, and he finally realized his dream. When Richard Avedon was assigned to photograph the sensational collection for Bazaar, he did so with a dressed-down restraint that was not typically found in fashion portraiture. One photo, a favorite of Avedon’s, was taken in Monsieur Dior’s workroom—a dress form stood next to the model, while a seamstress was at work in the background.

“There were plenty of beautiful Parisian backdrops that Avedon could have used for this gown, but it is no accident that he chose this spot,” writes Carol Squiers, a curator at the International Center of Photography in New York, in Avedon Fashion 1944-2000. “What better place to show that haute couture clothing was produced by hardworking, dedicated Parisian artists and that by supporting French couture, you were bolstering the ailing French economy, too?”

Squiers notes that Dior’s New Look “was an important element of France’s economic recovery, and such a success that it ‘represented 75% of the total export sales from France’s fashion industry for 1947.’” American magazines and their editors flocked to photograph Dior’s clothes, hoping to revive the previously shuttered Parisian fashion scene by featuring it in their pages. Snow proclaimed Christian Dior the “hero of the day.” In a way, he was—Fashion became one of France’s most crucial tools for economic recovery in the aftermath of the Occupation. Christian Dior was not just a brilliant designer; he was a patriot.

“There is no more futility in fashion than in poetry or song,” Dior once said. “And so, in this century, which has been attempting to destroy all of its most terrifying secrets, what occupation could be more praiseworthy than to create a lovely new secret every six months?”

Somewhere along the way—perhaps caught up in the obsessions of “product drops” and “it bags” and Instagram influencers—Fashion went chasing revenue above all. Now, in this time of crisis, many are realizing that any race for profit will eventually lead to the bottom. (Funny that it’s called the bottom line, isn’t it?) In turn, we’ve experienced the fastest revolving doors of hired-and-fired designers than ever before, where executive egos and social media strategies usurped even the most brilliant artists of our day. In turn, it’s no wonder the best we could get were bejeweled sneakers, a thousand identical iterations of a small leather handbag, and sweatshirts that cost as much as a down payment on a car.

In our grand disillusion, we lost touch with the fact that people don’t spend outrageous sums of money on a Dior dress or a Chanel purse because they actually think the item they buy is worth it. We know it’s not! We buy it because of the magic attached to it. It’s only inevitable that magic will be exactly what we crave again sometime in our future.

One day (maybe not anytime soon), we are going to be able to leave our houses again. We’re going to walk outdoors, meet our friends for dinner, and wrap them in a hug. We will wake up and get ready for the day—our first times back in society—where we will see other people, and remember what it was like to not fear them. But before we do that, before we re-join the ranks of our friends, families, and colleagues, we will make a decision that we will almost certainly weigh more thoughtfully than before: What will we wear? Here’s hoping we’ll have an abundance of magic to choose from.

This is an interesting exploration on what fashion will become in the "new" world. As one who has always been smitten with fashion, I had been agonizing of late when perusing the dailys and fashion rags, feeling disheartened to see that the best we can expect is a Disney character, a lion, or meme placed on the print of a beloved house; pieces that are fitted to appear that they are hand-me-downs from your great-uncle who served in WWII; yes, and sweatshirts twice your size with a price tag to astound. Should I feel less of myself that I don't own $150 undershirts or pay $15000 for an outer coat? Isn't that absurd?!

Hopefully this period of introspection will bleed into the fashion world and we will, once again, crave a beautifully crafted item that will stand the test of time; that will not, like our latest smartphone, be obsolete the minute we leave the store.

If not, I surely possess more than enough to last my lifetime.

I’ve been thinking a lot about this lately. How we move forward after this pandemic I think will dictate how responsive people are to fashion. I think people still love the magic. They just don’t know how it fits in their life at the moment. For me fashion is an expression of creativity and a physical representation or extension of myself. I forget that not everyone bears the confidence to go to Sephora and try the fuschia lip stick because it brings them joy and pair it with a set of gold hoops because they make them feel like queen on the daily. I think in a time when we are uncertain about our lives we forget that the people we should dressing for first is ourselves, and not everyone has tapped into that yet. Maybe this time of introspection will change that. Our buying habits will finally change as a result of this and I think the industry will have to respond accordingly. We’ll be back to a moment when people thought about keeping a garment for longer periods of time and buying less and possibly searching for a higher quality. I could talk for days about this, but all in all an excellent read.