What the HIV/AIDS Crisis Can Teach Us Now

Steven Thrasher examines the similarities (and crucial differences) between HIV and COVID-19.

Image courtesy of ACT UP New York.

Last week, I published a piece about the media’s omission of protests surrounding Samaritan’s Purse, an evangelical organization that set up tents in New York City’s Central Park. After speaking with members of ACT UP and Reclaim Pride, what I found was that LGBTQ+ activists have long been cast aside and ignored by mainstream institutions—even when their voices and insight would have proven invaluable.

A lot of queer activists are pointing out that the lessons we’ve learned from the (ongoing) HIV/AIDS Crisis are valuable in this moment. While coronavirus and HIV are vastly different, there are similarities to be found in who will be neglected, who will fall ill, and whose lives are deemed “worthy” by an ineffective federal government. This is an imperfect comparison, for sure, but it’s one that I’ve found worthy of visiting. After all, it seems like this moment in time is forcing all of us to take a good, hard look back.

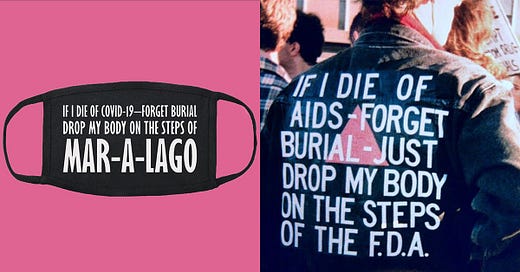

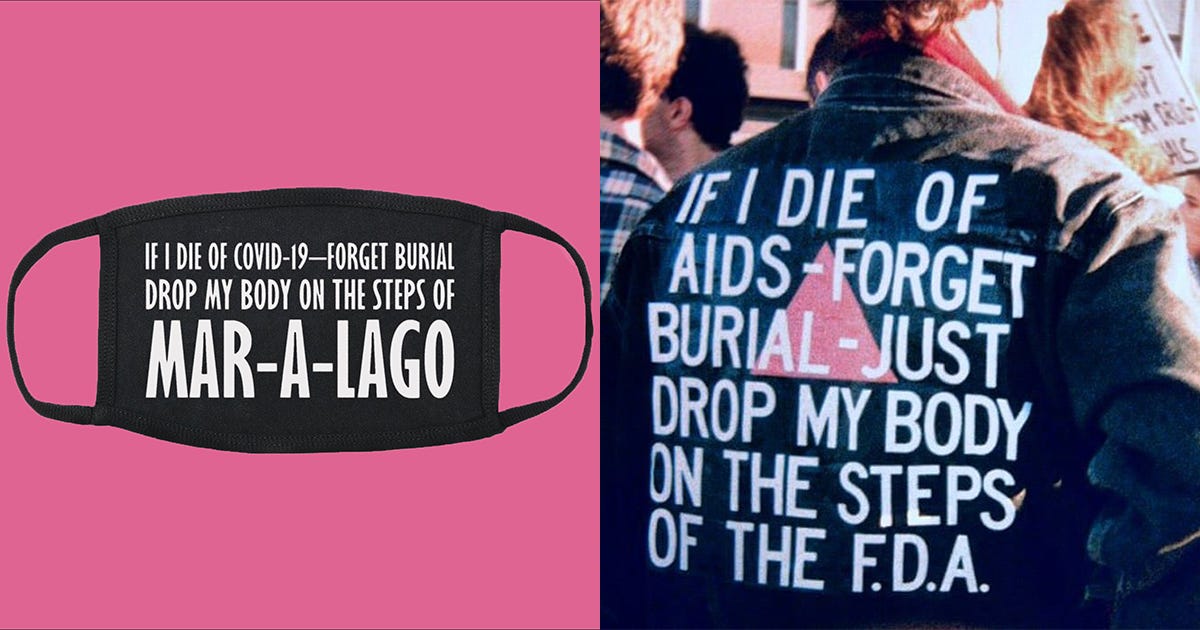

At the beginning of social distancing, ACT UP New York posted an image of a black face mask splayed across a bright pink background. The mask had text written atop it reading, “IF I DIE OF COVID-19—FORGET BURIAL. DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF MAR-A-LAGO.” The text was a reference to the late artist David Wojnarowicz, who wore a jacket reading, “IF I DIE OF AIDS—FORGET BURIAL—JUST DROP MY BODY ON THE STEPS OF THE F.D.A.”

Somewhat predictably, the new image caused an uproar on social media, and spawned a few articles pondering ACT UP’s comparison, the best of which (I think) was by Mathew Rodriguez at The Body. “The more the internet roared against ACT UP New York and the more I checked in with those I love, both inside and outside the group, I saw the need for the comparison, both of the images and of the epidemics,” he wrote.

At the time the image was released, this newsletter had not yet been born. Nonetheless, my friend Steven Thrasher agreed to speak with me about his reaction to the controversy. Steven is the Daniel Renberg Chair of Social Justice and Reporting at Northwestern University, and is also a faculty member of the Institute of Sexual and Gender Minority Health and Wellbeing. I find it fitting to publish our conversation today, since ACT UP kicks off a series of webinar discussions about COVID-19 and how we can all organize to fight injustice. Today at noon, Steven himself will be appearing on a Northwestern webinar to discuss the “global implications and futures” of the viruses.

It’s important to note that, since our discussion, there have been developments of COVID-19 that also beg comparison—notably, criminalization laws around the illnesses and Gilead’s role in bringing a possible treatment to market. If you’re looking for more information on either of these issues, I’m sure both of those things will be explored in greater depth in the webinars. For now, though, Dr. Thrasher explains the similarities and differences between coronavirus and HIV—and the activism that’s needed to solve the injustices brought about by both.

PP: I'm sure you've seen on social media lately that there has been a lot of conversation about some things that ACT UP New York tweeted drawing a comparison between the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the current situation we are facing with the new coronavirus.

I think it would be the most productive to start by asking you if you do think there are similarities, and wherein you think those lie, and then we can talk about the differences.

ST: I have followed this online and know a lot of the people involved, and I think it's a fine comparison. I retweeted the image because it gives lots of things to think about. The image came from David Wojnarowicz, who [had the slogan about] delivering his body [to the FDA] after he died, and then [ACT UP New York] recently compared that with COVID-19. I think the anger people feel right now is analogous to the anger that was felt in the ‘80s. It's not a one-to-one comparison, but there are some really interesting and helpful things to think about.

First, both crises are similar in that they're dealing with viruses—they're bringing this microscopic thing we can't see into the public consciousness that forces us to think about the nature of reality in ways we haven't before. Both of the viruses have incubation periods that don't track on to how we typically think about sickness and health. People are incubated with the virus and they may be transmitting, but they have no idea because they don't feel symptoms.

Second, during the early years of the Reagan administration, it did take President Reagan many years to say AIDS. Contrary to popular belief, it wasn't [true] that nothing was happening [relating to HIV/AIDS] in the Reagan White House; there was gross inaction, but there were actually lots of things happening. There’s a book, After the Wrath of God, which was about the fighting behind the scenes and the inaction from the administration. We saw a similar inaction from the Trump administration. When we are thinking about COVID, of course, everything happened much faster, but there was that crucial period of inaction.

Third, [the inaction regarding COVID-19] wasn't distinctly rooted in homophobia, but it was rooted in ableism and thinking that the people who would ultimately be affected were disposable. We heard that more recently when Trump contemplated re-opening the economy by Easter. I think this is quite similar to the attitudes around AIDS in the early days—there's this frame of austerity that's often used for all of this, and it justifies who should be able to live and who should die based on what the economy can “afford.”

This is kind of intersecting with my current research, where for the past few years I've been studying HIV criminalization and particularly looking at how the criminalization of HIV also tracks onto police violence and incarceration and homelessness—all things that affect Black America. I've started to understand that the same kinds of people keep getting made the most vulnerable again and again and again in different societies: immigrants, people in migrant camps, people who are incarcerated. These people are continuously made the most vulnerable to structural biologic health disparities, often under the excuse of austerity; that there was no money to be able to make them safer. Exactly the same thing is happening with [new coronavirus]: the people who are most vulnerable are lacking homes, they're incarcerated, they don't have jobs, and they don't have insurance.

Finally, what was drawing me into the potential comparisons between these two pandemics is the political possibilities. The HIV/AIDS activism in the ‘80s and early ‘90s spearheaded extremely original and powerful forms of protest—they were forms of protest and politics that affected society very broadly. The reason why trials have moved so fast for COVID is a direct link to reforms to testing that happened because of ACT UP and because of early AIDS activism. The way that AIDS activists affected scientists, who affected media, who affected lawmakers, in a very co-constitutive way—these cycles weren't just one affecting the other. There was this great sharing of knowledge that was happening between these different parts of society. A lot of them we don't necessarily see, like how drug trials and approvals happen, but lots of them we do see—like the use of single-use plastics [in medicine] and the way many things are sterilized in hospitals, or how your dental hygienist wears gloves. They wouldn't use gloves before they knew that there was this HIV virus. I think that we're going to see a similar kind of realignment of lots of different parts of daily, medical, and political life that happen out of [COVID-19].

PP: Thank you, that was so informative. There's a few more things before we move to the perceived differences that I want to ask you. There’s this idea that COVID-19 is here to teach us something, that to me has rung some bells, maybe recalling Christian fundamentalist language that was happening during the AIDS crisis. There's a belief that maybe this was supposed to happen, to teach us how to slow down, to reset Mother Nature, that we were living imbalanced lives. On its face, these kinds of platitudes can maybe seem nice on a Pinterest board, but digging deeper into it, some activists have actually called this mentality a form of ecofascism. They say this idea insists that marginalized people must suffer and die off in order to retain the prosperity of the wealthy. Do you see a similarity there, or am I drawing too far a line?

ST: Personally, as someone who does like to think about things sometimes from a spiritual dimension, I don't find it helpful to think that this was something we needed or something that was sent as a message, or that we have to find meaning in why it was sent. Rather, how we respond can be very revelatory and can help us understand ways we could be better in the world. We should think about how we act when something like this happens, and what that reveals about our societies and how they operate.

I don't try to make meaning out of how the virus came to be. My interest is much more in how a virus moves through society, and why it replicates itself in unjust ways. I try to seek meaning on that side of the equation. I have tried to think about the spiritual or historical dimension—that this is the first time in the history of humanity when you can talk to anyone anywhere in the world and they're going through some version of the same thing. Never before in my life have I been able to talk to people on four or five continents and everyone's kind of in the same experience in some way.

That relates to some of what I've read about AIDS activism. Coming through a horrific plague is not something anyone would wish upon themselves, their community, or any others. But having gone through it, there is the opportunity to say, as Vito Russo did in his great speech, “after we kick the shit out of this disease, we're all going to be alive to kick the shit out of this system, so that this never happens again.”

“If we are to keep mass numbers of people from dying, we're going to have to really be in people's faces in ways that unsettle them and make them extremely uncomfortable, and maybe even make them angry.”

PP: One other thing I’ve noticed: Trump insists on calling COVID-19 "the Chinese virus," and talks about China practically every time the virus is brought up. I interpret this as another form of his xenophobia. In his strategy, there seems to be an idea that he can make a villain out of China and lay the blame for the virus on China—and in turn, deflect the blame from himself. I wonder if that at all speaks to you in terms of what we know about Reagan and Bush and their ties to evangelical Christians or the Catholic Church, and their reluctance to be more proactive in fighting HIV/AIDS.

ST: I can speak to the nationalist ideas about ableism and race, which are tracking in very related ways with AIDS and COVID. My dissertation on HIV criminalization is called "Infectious Blackness."

The idea of the US as a disease-free space until it was invaded by certain diseases is something that has existed throughout our history. The US has considered itself free of HIV/AIDS until it was “invaded” by Haiti and [nations in] Africa. Even recently, Trump was quoted in news reports as having said, in a reference to “shithole countries,” that all Haitians have AIDS. This idea that the US has been infected by a sickness that's also very Black has been around for decades, and still exists in the current administration.

There’s something quite similar happening with the novel coronavirus when it's imagined as Asian, and we've seen this in the way Trump has talked about it. We've seen it in the anti-Asian American racism. We saw it when there was a real drop-off at Chinese restaurants and markets before social distancing started.

We conflate ideas of whiteness with ableism and health, and this is a huge part of our American history. I think Trump articulates it and personifies it in very distinct ways, and he also advances it and makes it worse, but it is not unique to him. He is a symptom of forces that have been happening for a long time. This mentality not only brings great harm to people of those identities, but it actually makes it harder to clinically understand what's happening in terms of transmission and assessing the best public health responses to the crisis.

PP: Absolutely. Now, what about the important differences and distinctions that we make between the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the COVID pandemic, especially when we're talking or trying to draw those similarities?

ST: First, I think it's helpful to literally start at the level of the two viruses: they're very different. HIV is a relatively inefficient virus—it has a difficult time moving between different people. Even at the level of the activities that we think of as the most dangerous, which is receptive anal intercourse without a condom, it's a very, very, very small number of times that transmission actually occurs. Then, if it does occur, it can take seven to 15 years for symptoms to start showing up and to become very dangerous. I said before that both viruses have incubation periods, but those periods are very, very different: The whole cycle of the coronavirus seems to be happening in weeks, and the effects sometimes days. People either feel symptoms or they don't. So they're on very different scales.

Second, the human immunodeficiency virus has been located in specific communities around the world. Sometimes they share traits, sometimes they're different. But the way that we first started seeing it in any concentration was amongst gay men and then amongst users of intravenous drugs at that stage, and then hemophiliacs. It's increasingly become concentrated amongst African Americans and Black people in the US, largely because, once medication became available in the late 1990s, white America got the medication much, much, much more broadly than Black America did. Then, it became more concentrated in Black America. Elsewhere in the world, HIV has been, for the most part, in concentrated populations who were at risk.

On the other hand, coronavirus is spreading much more generally [throughout the population]. It happens through casual contact, it happens through touch, it happens through surface germs. These were all fears of HIV that were not true: You can't transmit HIV through hugs or handshakes. But COVID can move very quickly through casual contact, so that's something to keep in mind about how they're very, very different.

Finally, I think one of the things that people who lived through the epidemic of AIDS and HIV in the early ‘80s and ‘90s might be attune to is that the public response has been much more general. There's probably some memory of being despised, particularly for being queer or for being users of IV drugs. There's probably real memory there of trying to martial interest when the government didn't care about them. Now, people can become positive with COVID in ways that don't involve shame around sex necessarily, or don't involve the shame around queerness. But again, I do think there are overlapping issues here.

PP: As one of your differences, you mentioned the access to medication being a big factor. I wanted to dive in on this because my understanding is that Gilead has an involvement in medications and vaccinations for COVID-19.

[For readers who aren’t familiar: Gilead is the pharmaceutical company that produces Descovy and Truvada, two pre-exposure prophylactic drugs that help to prevent the transmission of HIV. When PrEP, as it’s called, was first released at market, it was exorbitantly expensive; some estimates tally it at over $2,000 for a month’s prescription for those without insurance. Outrage ensued, partially because Gilead used taxpayer dollars to fund the trials for the drug, yet still controlled its patents and pricing. In the years since PrEP has hit the market, transmission rates among gay white men have fallen. Meanwhile, Black and Latinx gay men make up the largest amount of new HIV diagnoses and rates of diagnoses are actually increasing among Black women. After much protest, Gilead pledged to make Truvada available more affordably by September of this year. They then released Descovy, a practically identical drug they are marketing as “more effective,” despite doctors’ claims to the contrary.]

On the one hand, Gilead has access to a drug called remdesivir that is still in trials to assess its full efficacy in treating COVID. This is now resulting in people hoarding the drug, and limited access becoming an issue in our hospitals. Of course, Gilead owns the patents to remdesivir which, once again, was funded by United States taxpayers to the tune of $79 million. Obviously, this is a big parallel we can draw—this one pharmaceutical company controlling access to a medication, potentially having the ability to price gouge it, and therefore making it inaccessible to the people who really needed it the most. Am I far off here?

ST: No, I think you're understanding it about as well as I am. I'm not privy to all the dimensions of Gilead, but I admired and watched how ACT UP has been hammering them on holding the patents longer than they should have on HIV medication, and how they've been trying to push people from TRUVADA to Descovy. It's been hella exciting to see [Congresswoman] Alexandria Ocasio Cortez really take on Gilead and ask, “Why is the pill eight dollars a month in Australia, but $2000 a month in the United States?” Looking towards what ACT UP has done historically but is still trying to do now is going to be really important, because Gilead is going to try to win this same race with COVID-19. They're going to push really hard to maintain the private insurance system, a system which—on a day when over three million people lost their jobs and probably most of them their health insurance—is a system that we cannot let continue.

PP: Before I let you go, Dr. Thrasher, I just wanted to close by reflecting on what you mentioned about the controversial imagery that ACT UP created. A lot of this imagery was, as you alluded to, deliberately antagonistic, deliberately provocative. I can imagine that the reaction to it back then was not always very warmly received. It was that kind of reaction that was crossing my mind when ACT UP's tweet hit my timeline, because I initially doubled back. I really actually paused to look at it and to process how it made me feel. Do you think that seeking that reaction is helpful in a time like this?

ST: With reactions, I think we should just honor what they are. They're not always predictable. I think as you were just stopping and thinking about it, that's a good way to be with something that feels shocking to us. I think there's something really generative to contemplating how shocking what ACT UP did was, and how palatable gay political messaging has become, right? When ACT UP was first creating its messages, it was trying to be extremely shocking and in your face. So much of gay messaging and branding has been designed, over the past few decades and particularly over the last few years, to be comfortable, to be as unobtrusive as possible. So much of the gay messaging we see is on ads for banks or airlines or things like that.

I show students scenes from the two ACT UP documentaries, United in Anger, which was made by the ACT UP oral history project, and the movie How to Survive a Plague.

They both have footage of a protest at the White House in '91 or '92, where activists take the ashes of their dead loved ones and just throw them onto the White House lawn. It is so hard to wrap my brain around the fact that such an activity would happen, right? Like even the fact that they could get that close to the White House, that they could throw these ashes onto the lawn! To revisit what ACT UP was actually doing is to realize that they were extremely confrontational. It was not party aligned. That's a real big difference of gay politics now: so often today it's aligned with the Democratic party. But it was not always.

When I think back on the major gay political things I have covered in my career as a journalist over the past decade—same-sex marriage, military service, employment protection—you don't see anything that provocative, right? You see things that, for the most part, reaffirm ideas about work, military service, marriage, and institutions. I'm not saying it's bad, it's just different. Today, I don't think that we are used to having stuff in our faces as much.

But I think if we are to keep mass numbers of people from dying, we're going to have to really be in people's faces in ways that unsettle them and make them extremely uncomfortable, and maybe even make them angry.