Today, We Graduate

Our diplomas are meant to be a promise for our futures. But what future is that, exactly?

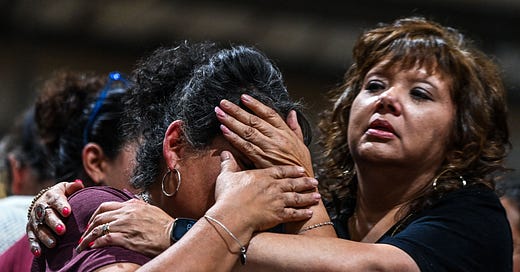

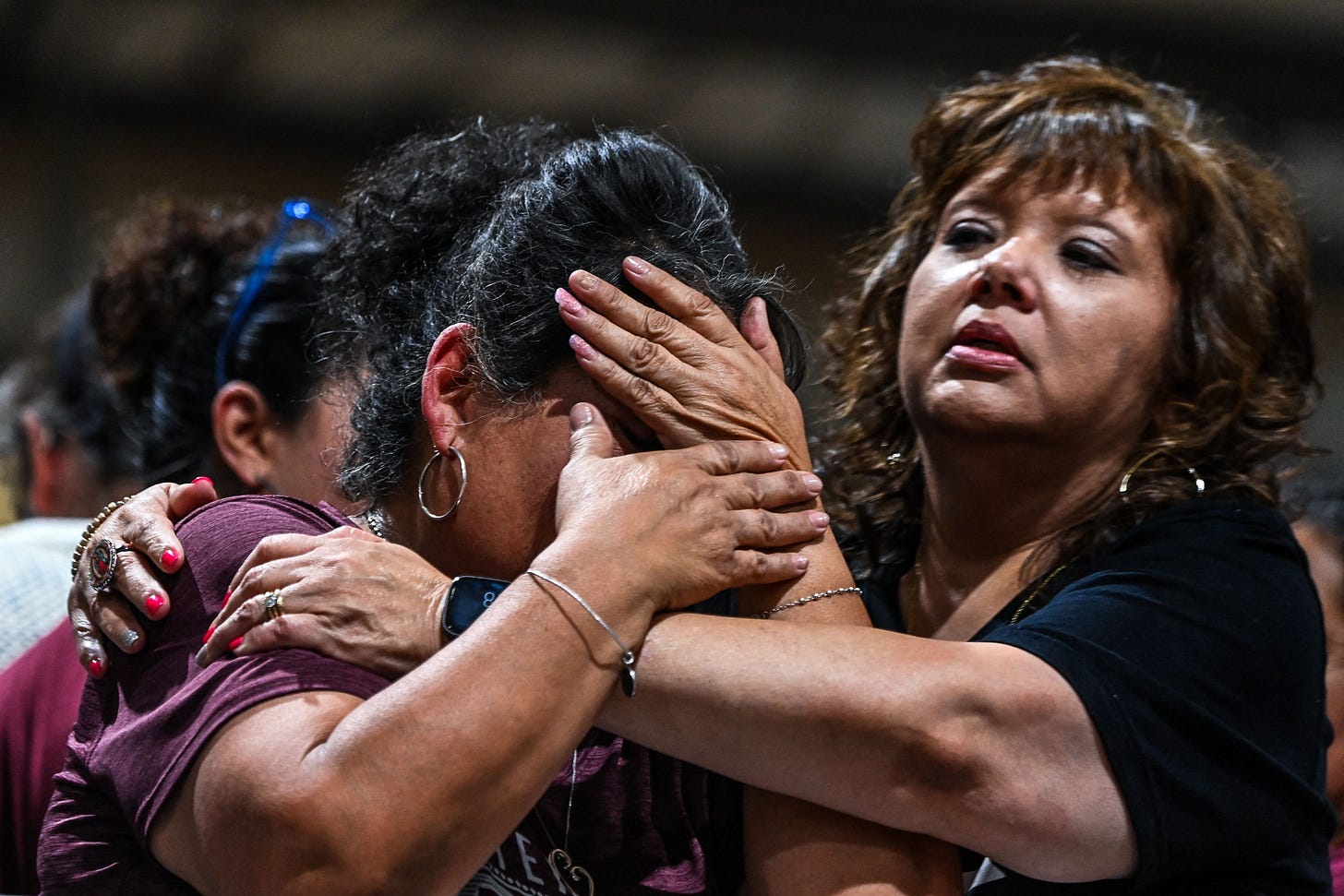

Photo: Getty Images

For the first time in three years, Harvard University is celebrating its commencement activities today in person. As I write this, Jacinda Ardern is probably taking the stage at Harvard Yard to address an audience of over 30,000 people. Commencement is about celebration, of course—many of the students gathered today have worked incredibly hard to reach this proverbial finish line. Their families and loved ones have sacrificed—some more than others—to even get their graduate to this outrageously expensive institution in the first place. The diploma we receive today is meant to be proof on paper: We earned it, and because we earned this, good things are to come.

Unfortunately, that’s a promise that has never felt more vacant than ever. While the university prepared for a week of jubilation, countless people in our nation grieved horrific tragedies. First, a mass shooting in Buffalo by a white supremacist who targeted Black people doing their grocery shopping. Then, a killing spree in Texas targeting elementary school children and their teachers. Images of families weeping flooded our television and phone screens. Meanwhile, the American death machine continued churning in the background: legislation banning abortion in Oklahoma moved forward, as did bills targeting the rights of transgender youth. Books that tell our stories are being removed from school libraries at the same time that Republican lawmakers call for the arming of schoolteachers—teachers who, just last week, were being accused of “indoctrinating” young people into an “LGBTQ+ agenda.” This is to say nothing of the gun violence that has never stopped plaguing Black people in America—guns wielded by police officers whose power and resources have gone virtually unchecked and unchanged since Black Lives Matter began protesting almost a decade ago.

Many of us are waking up to the fact that things are quite scary and are only getting worse in this country. For the more empathetic among us, this is frustrating on a deeply moral level: We are now realizing that the people who warned us the worst was yet to come were right all along. Hopefully we can also realize that, if we’re just becoming aware of the atrocities of this country, we were never giving its cruel dimensions our full attention at all.

There’s a common notion that we are “backsliding.” I have a hard time accepting this idea—it implies progress is linear, and that things were once better than they are now. The question is always: For who? Some of the “wins” currently being unraveled by the Supreme Court (from marriage equality to Roe) are exposing how our mainstream political movements always sacrificed the most marginalized to reach their resolution. The grip that the white supremacist Christian right has on our courts and our politicians exposes the fallacy of our belief in secularism. And “following the money” of the NRA, or the oil industry, or Big Tech exposes the pitfalls of capitalism. We have grown weary of being told to vote, maybe because civic engagement can feel futile in the face of a system that is clearly rigged against us. “Backsliding” feels inadequate, if not entirely incorrect. In many ways, the American project appears to be reaping what it has sowed.

And yet here we are, in our polyester robes and our tasseled hats, graduating anyway. We are crossing a stage that the students of Robb Elementary School will never get the chance to. We attended a year of classes without a single lockdown drill—a luxury they and many other American schoolchildren never had. We are, as every commencement speaker loves to say, about to embark on the rest of our lives—while their families mourn the possibilities of theirs. We are, as the poet Saeed Jones puts it, alive at the end of the world.

The Harvard College student Treasure Brooks has spent a considerable amount of time exploring the concept of “luck.” A lot of people in America, for example, say they are “lucky” to be born here as opposed to another country with less wealth or resources. “Eat your food,” my friend advises her children, “because there are kids in other countries who are going without.” We sometimes spend time exploring the idea of this supposed wheel of fortune—how did we get born here, but another baby somewhere else gets born into plague, war, or famine? This idea, she explained, ignores accountability. Those people aren’t simply “born into” less favorable situations. They are born into conditions that, in many cases, America—through its weaponry, its war-making, its imperialist agenda—has helped to create. Those of us who have escaped the horror of mass shootings might consider ourselves “lucky.” This is an insult to the families who have lost their loved ones. In one way or another, we have all agreed to live in a society where the mass murder of children is acceptable, where a gun is less regulated than a woman’s body. This hardly makes any of us lucky at all.

While Treasure urges us to recontextualize “luck,” I want to urge us to recontextualize faith. Maybe we had faith when Joe Biden was elected that things would get better, or that the nation would start to heal. Or we had faith, in the wake of countless demonstrations, that Congress would finally do something about police brutality. Perhaps some of that faith has been misplaced. We’ve still clung to placing it in institutions, or the elite, instead of placing it in each other.

My time at Harvard Divinity School has taught me a lot about why people cling to faith. My guess is that more of us will search for spirituality in the years to come—not because religion is some passing trend, but because the circumstances of our world are almost certain to get worse before they get better. After all, religion knows the end of the world better than any other field of study. Even if democracy survives, we’ll still have to contend with the continued destruction of our planet, which is going to require more empathy than ever for the poor people, the displaced, and the creatures we share this Earth with. We live in “Biblical times,” people point out with humor. But people “in Biblical times” often show us a different utilization of faith than the one we’ve grown accustomed to.

People are utilizing faith to accomplish deadly, destructive things—look no further than the terrorism of the religious right in America for a prime example. Religion might sometimes coax us into believing that God has the final plan, and all will work out as it’s intended. It can be like the cat sitting on our laps, warmly purring us into passivity. If we let it, Faith can be different. Faith can turn our thoughts and prayers into action—into a righteous, ancestral anger that makes the powerful tremble. If we are to live in fear, why should our politicians and billionaires live with so much ease and comfort? If their constituents and employees know no peace, neither should they. Our modern Pharaohs need dethroning, our empires need challenging. And we, the people, need to fight back against their merciless crucifixions of our loved ones.

If this is indeed the end of the world—like the poets, the Evangelicals, and the prophets are saying it is—then we need to start acting like it. We need to peel our eyes away from our phones and unshackle ourselves from these predatory algorithms. We need to gather with our neighbors and our loved ones, not just to plan protests or actions, but to build community and safety and foster hope. We need to—all of us, even the non-biological parents—raise our young ones to be happy, hopeful, strong, and brave. And we will need to seize joy whenever we can—to celebrate ferociously and jubilantly, like it’s the last time we might ever hold each other. I hope that’s what today can be for our graduates.

If this series of distinctly American tragedies can teach us anything, it’s that no future is ever promised. But even that can be a trap: it tells us that there’s nothing we can do, so we can just let go and dance or retreat to our bunkers while the world burns. Or we can try, with whatever Faith we can still muster, to build a different future. We can no longer walk into the rest of our lives with complacency and passivity in the hopes that what is for us will come. We can no longer count on living the lives our parents or grandparents hoped for us. Instead, we must band together and forge something new. It will be hard, terrifying, and sometimes even dangerous.

Faith—even if it’s not about God, but simply about Faith in one another—can give us something worth fighting for. Instead of coasting into the flames at the end of the world, we can walk through them. We can let their licks purify us, their destruction give us new soil. We can insist on tomorrow. If not for ourselves, than for those we lost along the way, and those who deserve a chance at forging their own futures. To do anything less is to let those children die in vain. We cannot be willing to go quietly. Because if we are together, our faith unwavering, we can’t lose.

You have been on my mind Phill, thinking about the work we did together around gun violence, as well as bullying. Thank you for this and all. You continue to inspire and amaze me.