How Religion Can Be Used to Build a New Future

Building a more complex understanding of religion may help us better understand violence—and, in turn, work together to eradicate it.

Photo: Getty Images

Ok, y’all: We are finally here on the last day of this newsletter (for now). Tomorrow morning, I head back to Los Angeles for a brief respite before returning for graduation. You might get another inbox from me around then.

If you’re still with me, I hope you enjoy the last part of my thesis. It’s a two-parter, but I think they are essential to be read together for the conclusion.

To recap: I opened this series with an introductory question: Do We Really Want to Give God Away? Then, I introduced us to the importance of challenging “normative” ideas in our culture, using “objectivity” in journalism as an example. After, I asked us to challenge two big, normative ideas that inform how we view religion: secularism and the conception of “the East vs. the West.” And yesterday, I asked us to challenge absolutist claims about religion. Today, we’re going to finish by identifying how challenging absolutist claims helps us to better identify how religion is wielded as a category of power. By better understanding the interplay of violence in our society, we might be able to better implement peace. I finish the thesis with a call to action about continuing to challenge the common understanding of religion in order to build a better future.

Thanks for coming along with me on this journey, and I hope this conclusion has been satisfying enough. If you’d like me to host a Q&A in the near future on this platform, please let me know. You can also check out my Instagram for a Q&A with the author Cleo Wade, where we discuss some of these topics more broadly.

4: Challenging essentialist claims is not meant to absolve religion—rather, it helps us understand how religion is embedded within societal power structures.

Our intention in moving away from religious essentialism is not to activate some sort of PR crisis strategy for the faiths of the world. By adding complexity to these claims, we are (1) making sure to not erase the diversity of religions and their followers; (2) adding to the understanding that religion is just one of many interconnected sociocultural systems that contributes to how power operates; and (3) building a situated knowledge about religion and power that will help us to better understand violence, and work toward creating peace.

The Violence Triangle

First, it’s important to understand the many faces of violence and how it intersects with categories of power. We can easily understand physical assault as violent, but we might have a harder time naming beliefs, ideologies, or policies as such. The peace philosopher Johan Galtung believes that violence can fall under three important categories, all of which impact the other in what’s known as the Violence Triangle.

Side (1) of the triangle is cultural violence, which speaks to harmful norms or beliefs (for example: “immigrants are going to steal our jobs”) that can help make direct or structural violence seem justified. (2) Structural violence is systemic harm, and therefore comes from institutions or bodies of power, be it government (ie: policy like segregation), the academy (educational inequities in public vs. charter schools), healthcare (poor people receiving lower standards of care), and so forth. This can lead to both cultural violence (since institutions can help create or validate cultural norms) and direct violence. (3) Direct violence immediately threatens a life on the basic level: assault, murder, abuse, et cetera.

One of the ways we’re currently witnessing the Violence Triangle play out with startling swiftness is on the matter of transgender rights. This example is salient because religion is one of many factors that has led to a tidal wave of anti-trans rhetoric (cultural violence), legislation (structural violence), and murder (direct violence) that is inadequately being recognized in the mainstream. Unlike the gay marriage discourse of previous decades, religion does not always play a front-and-center role in much of the current anti-trans rhetoric—but it’s absolutely present.

How Modern Transphobia Animates the Violence Triangle

The genealogy of transphobia would take an entire book to discuss, but one of its main components is the construct of the gender binary (and additionally, the conflation of gender with biological sex), which I’d argue is a form of cultural violence. Western cultural norms assert that there is man and woman, and that this is a “common sense” argument for denying the validity of the existence of transgender people. These norms have been propped up by science (the concept of biological sex), religion (to take the Christian example: God created man and woman in Genesis), and society (gender roles, fashion and beauty, et cetera). However, the gender binary can be analyzed as another absolutist construct. After all, it was never a complete or inclusive system for encapsulating the complexities of sex or gender, and many people in our world have been erased and oppressed by this construct. For one thing, certain indigenous communities in North America, the Pacific Islands, South Asia, and elsewhere have historically held space for gender variations and categories beyond the binary. For another, intersex is a scientifically recognized category of sex in the West that is conveniently left out of our conversations on gender and biological sex—which has led to different forms of structural and direct violence for intersex people. And finally, transgender people are not a new phenomenon of Western invention, but the stigma that accompanies deviation from the binary has led to trans individuals’ increased marginalization, misrepresentation, and lack of visibility. Regardless, anti-trans rhetoric clings to the gender binary as an immutable fact. This argument has caught flame thanks to its amplification by many notable people who hold positions of power, including Harry Potter author J.K. Rowling, the tennis player Martina Navratilova, and various conservative commentators.

Before some of the “trans debates” were taking place with the frequency and fervor they are now, transgender people in America (and the UK, where much of this rhetoric has taken a mainstream hold) already faced alarming rates of structural violence—including disproportionate rates of poverty, homelessness, and unemployment. As the fervor escalated, a whole new suite of structural violence was unleashed: Over 100 anti-trans bills were created across America between 2019 and 2021, some of which inspired Florida’s infamous “Don’t Say Gay” bill. Alabama now criminalizes gender-affirming care for transgender youth. The inundation of legislation illustrates how cultural and structural violence feed off each other. It’s easy to see how conservative lawmakers descended on a hot button issue that could appease their base and therefore keep them in power. On the flipside, people who were once ambivalent about or unaware of transgender equality are now being inundated with transphobic headlines from the news media and bigoted rhetoric from their elected officials, school boards, and legislatures. This has helped to fan the flames of a moral panic—a fear that the trans “agenda” is to turn all children trans—and it’s being employed to justify extreme measures to control the community.

What has gotten buried in the headlines of these cultural and structural wars is Galtung’s articulation of direct violence. Suicide and crisis hotlines like The Trevor Project and Trans Lifeline report dramatic upticks in phone calls from young queer and trans people when legislation targets their home state. Additionally, 2021 marked the deadliest year on record for transgender people, with 47 reported killings in the United States alone. Across the pond in the UK, hate crimes against transgender people have doubled in the span of five years. This is to say nothing for the countless unreported assaults on transgender people who might be loath to report crimes for fear of discrimination by law enforcement, or the misreporting of violent crimes against trans people by police and journalists who insist on using birth names and incorrect pronouns in obituaries and coroners’ reports.

With all of this in perspective, it’s easy to identify how transphobic direct violence (assaults, hate crimes, murders) is influenced by cultural transphobia (rigid enforcement of the gender binary, erasure of trans people in the public square) and structural transphobia (laws barring gender-affirming healthcare for transgender youth, or removing access to public bathrooms). All of these forces act together and influence one another to perpetuate violence in our society. Situating violence in this way is helpful for how we criticize or engage with religion, because it allows us to understand the many animating forces that lead to violence. Instead of laying blame in one direction (Republicans! The religious right! Trump supporters!), we develop a more robust understanding of the root causes and history of the issues. It’s only once this happens that we can start to identify how to promote peace.

By Properly Diagnosing Violence, We Can Better Understand How to Achieve Peace

Luckily, Galtung proposes that just as violence exists in a tripartite system, so does peace. (It’s important to note that Galtung had two conceptions of peace: there’s negative peace, which is the absence of war or violence, and positive peace, which is built by lasting, sustainable investments in relationships, structures, and societal attitudes.) Currently, trans activists are working to build a coalition with reproductive justice efforts across America, since both are under attack in our legislative and judicial system. This intersection is an interesting one for promoting peace within Galtung’s theory.

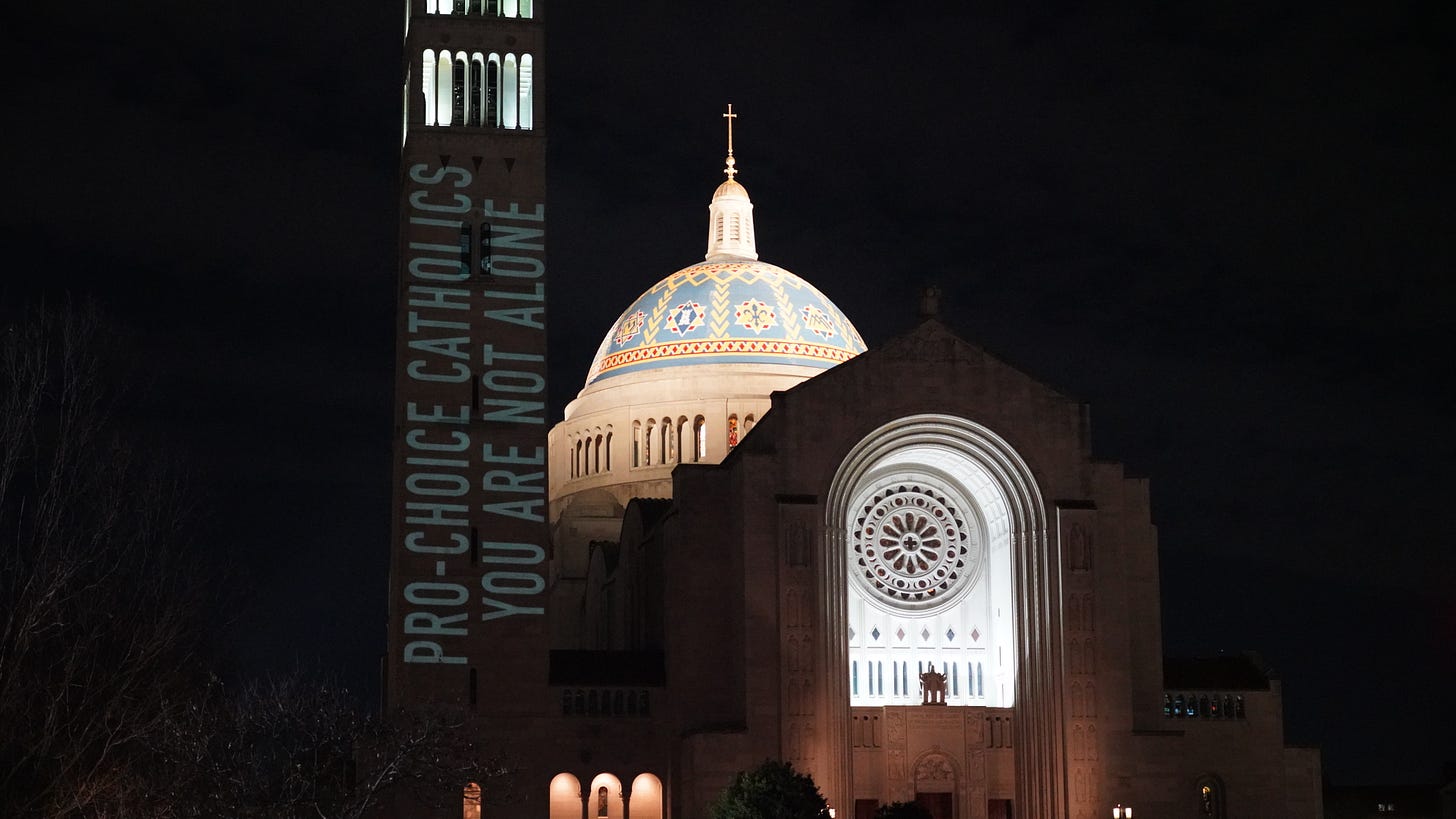

First and foremost, trans activists linking arms with reproductive justice activists promotes cultural peace: the coalition illustrates how these fights are linked under a common umbrella of gender justice and bodily autonomy. This strategic move helps to arm cisgender women with the knowledge that transgender people have been long left out of the conversations surrounding gender-based violence and reproductive care. It shows an area of common ground and shared experience, and allows both factions to understand how showing up for each other’s autonomy helps to make their collective fight stronger. Of course, many religious people support the right to choose (Catholics for Choice is just one example of how faith groups can challenge a broader religious institution), so employing the power of bodily autonomy in religious or faith speech can help others understand how this issue applies to their own personal beliefs. This coalition can help bring about structural peace through large-scale organizing, fundraising, and resource pooling to increase leverage and strength in the fight for their rights. Finally, direct peace is brought about by the coalition’s fundraising, mutual aid, and community building. These are all examples of promoting peace not necessarily by changing the hearts and minds of “the other side,” but by situating violence in a way that helps us realize who, exactly, is most victimized by abuses of power—and how we can rise together to fight back.

TL;DR

Religion is just one of many categories of power that can inform violence in the world—be it structural, cultural, or direct. When we understand these kinds of violence as interrelated, we can better work towards dismantling it and creating peace.

5: When we throw our hands up at religion and flatten its role in our lives, societies, and institutions, we allow hegemonic power to go unchecked.

As the critic Saba Mahmood says: “To critique a particular normative regime is not to reject or condemn it; rather, by analyzing its regulatory and productive dimensions, one only deprives it of innocence and neutrality so as to craft, perhaps, a different future.”

To imagine a different future, a more complicated view of religion can be a powerful tool. Essentialism around religion and faith does not just paint an inaccurate picture of the system or the world, it also allows this massively powerful force to be wielded by a group of people with a singular aim or agenda. If religion has become synonymous with violence or regression or injustice, it’s not just because it is embedded in so many matrices of power. It’s also because the people who are challenging the hegemony and seeking to carve out a different future have been overlooked, erased, or ignored. This is the destructive power of cultural norms.

One doesn’t have to be religious to want to uplift the ways that faith and the faithful are working—right now, at this very moment—to stop our wars, to house our homeless, to heal our sick, to mourn our dead, to challenge the ills of empires, to comfort our dying, to sanctify our love, or to celebrate our new life. Understanding religion’s immense power and influence might just help us identify how to wield it toward a different, more equitable future.

One of the most compelling things about religion is that its sacred texts reveal so much to us about the power that lives in the stories we tell. If we can start to change the story we tell ourselves and each other about religion—to illustrate its destructiveness and its seductiveness, its capacity for informing rigidity and rebellion—we may be able to finally write the different future we so badly need.

❗️❗️❗️ “when we understand the violence we have interred.” so much of living in the modern world has been to erase of memories of our violences. this reminded me of one of my favorite episodes of Dr. Who; sharing with everyone post haste!